Richard Hedderman – 3 Poems

Cellar

On a winter afternoon, I went down to the cellar

To put away my work boots, and the old dreadnaught

with the faux ivory inlay on the fretboard. There

was a pain in my shoulder— I don’t remember

which one—that felt as if it had been there

for a hundred and fifty years. In the cupboard

under the stairs were shelves of cherries and onions

in jars, and half-full bottles of whiskey

from distilleries shuttered during Prohibition.

At least that’s how I heard the spiders tell it,

descending invisible threads

from my grandfather’s broken fishing rod.

Dogs Of The Quarantined

We just quit barking, perplexed

By the unusual silence of our masters.

The newspapers that once swatted

Our noses, now lay unfolded

Beneath our water bowls. For once

They don’t hurry us to go. They

No longer look at the sky. We

Have to wonder if we are still

Their loyal sidekicks, or just someone

To lead them back home

After another of these aimless

Walks. The courage of our wolf

Forbearers starts to rise

In our throats, and all at once

We smell the snow

As if for the first time.

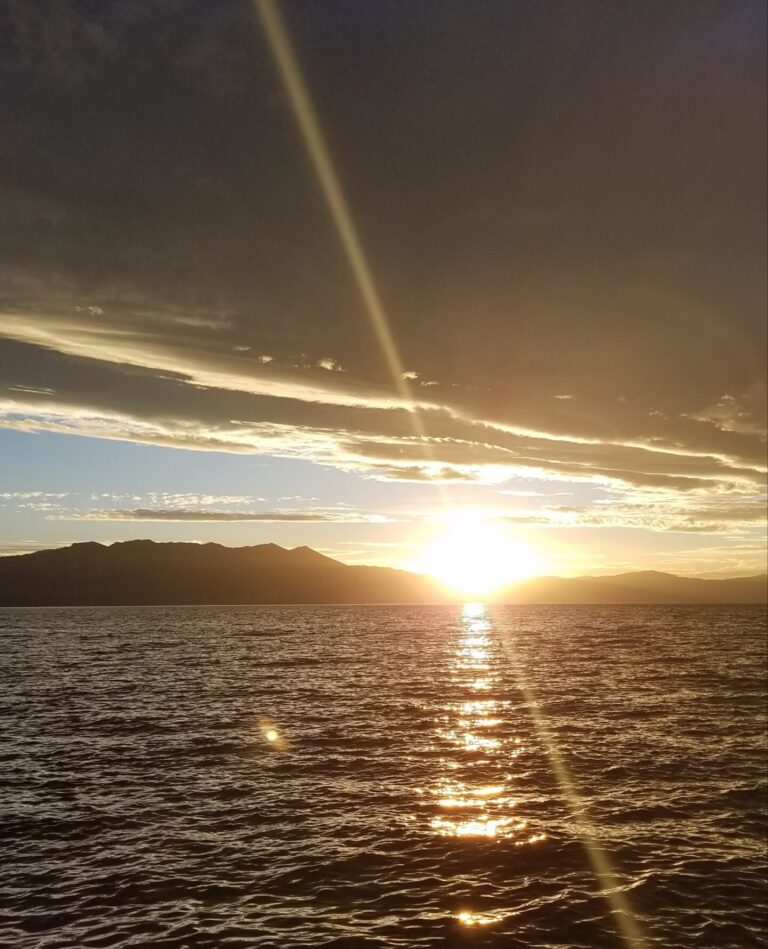

Dead Reckoning

I was led down a long corridor

passing doors marked, “Authorized

Personnel Only.” It grew darker

with every step. It was the first day

of my hunger strike, and I wanted

to get back as soon as possible.

By the time the passageway went

completely dark, I couldn’t remember

where we’d started—a prison graveyard?

A city square with shuttered windows?

Perhaps a muddy backyard in a country

village where a dog chained to a stake

shivered in fear as the widow hung

her husband’s shirts on a clothesline.