Bukowski at 100

“All you need is what you have. Work it.”

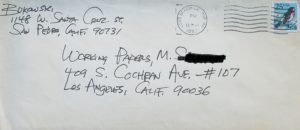

Then, a fellow traveler, a golden-winged warbler from Louisiana who owned a bookstore in Westwood, California must’ve felt sorry watching us ruffle our feathers over this doomed endeavor because she pulled out her secret “bookstore owner’s black book” one afternoon and handed over the address for the writer Charles Bukowski. “I can’t promise he’ll write back,” she warned, “but give it a shot.” A shot is all anyone can ask for in this life, so we took that address, wrote a special note on the back of a WP flyer and sent it off to San Pedro, expecting nothing.

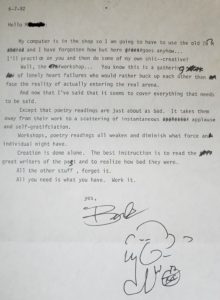

A few months later, we found a thick envelope in the mailbox, addressed to “Working Papers.” It was from San Pedro and “Bukowski” was elegantly scrawled in thick black ink atop the return address in the upper left corner. Surely this was a practical joke, from that Irish Redwing thrush named Mackie; a prank by the mischievous warbler who owned the Westwood bookstore. Still, there was an irregular heartbeat as the envelope was ripped open. And inside the envelope?

Grace. And nothing short of it.

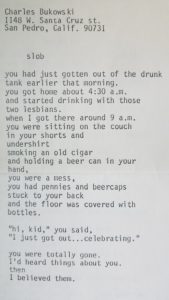

By 1990, Henry Charles Bukowski from San Pedro, California by way of Andernach, Germany was an international legend. Dozens of his short stories, novels, poetry collections and essays were being published regularly around the world in multiple languages. He had made it! Yet he had taken the steps of typing his full name and address at the top of a sheet of paper that contained a fresh, never-before-published poem, custom written to WP’s guidelines – like he was no more than just another struggling poet looking to get his work into print; like all of us! And not just one poem – two! If that wasn’t enough to confirm his generosity and humility – sending new poems to a magazine that hadn’t even printed its first issue – he had included a stamped, self-addressed envelope as well, in case his poems were rejected. He took nothing for granted; expected no special treatment. It was stunning.

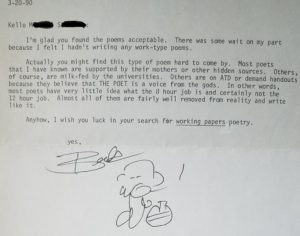

To make sure this was no joke, a thank you letter to thank was sent. He wrote back immediately, happy that we found the poems acceptable and warning that finding poets and writers who actually work for a living was going to be nearly impossible, but wished us luck anyway. Turned out he was right. Working Papers never got off the ground. Over the course of a year, less than a handful of submissions arrived. The firefighters, the cops, the minor league baseball players, they were busy working.

A couple of years later, after continuing to exchange correspondence with Bukowski on writing and writers, he sent words of encouragement and advice for all writers of any age and at any stage in their writing life: “All you need is what you have. Work it.”