Lisa Segal – Three Poems

My shirt and jeans are off.

I’m undressing.

I’m closing this day down.

OLD MATH

My shirt and jeans are off.

I’m undressing.

I’m closing this day down.

I’m going to bury the day’s remnants,

like a pearl oyster embeds irritants in its nacre,

even though, in the night, my pelvic bone’s

cartographical topography

cradles my dreams, and twist by turn,

the top sheet entangles my ankles,

letting the shroud of my body

hold me in a twin shape

I sometimes mistake for myself.

Like that summer I was twenty-eight,

trying to add What’s-His-Name to my equation.

Shopping with him at the grocery store,

we saw the woman who was still his wife.

Tell her! I said to him.

Tell her now!

Tell her now!

But he didn’t tell her.

He never told her,

and all the sepia,

all the elongated desire,

all that was built

on the vast plains of my simple math,

leaked out of me

like hydrogen sulfide.

One day, finally, I left him

sitting at Pan Pacific Park as dusk

fell across Beverly and Third,

lingered over the Tar Pits

and draped the Farmers Market

with shafts of darkness

that enclosed the parking lot and nursery

where the Grove is now.

Car exhaust pressed into my lungs as I ran,

my calculations evaporating

like the fry oil from El Coyote

as it floats down the street of a city

that rewrites the story

until it finds a producer

to fund it.

THE SWIMMER

The air conditioning clicks on.

Phoenix heat presses

against the blue-framed windows

that line my eighth-grade classroom.

It still seems like summer—the heat,

my dark hair reddish from chlorine,

my skin the color of date pits.

I’m at my desk,

a mimeographed test

in front of me,

a yellow pencil

in my hand

Twenty specific minutes

have begun to slip away.

I lift the top sheet.

It’s filled with questions.

I have my own questions:

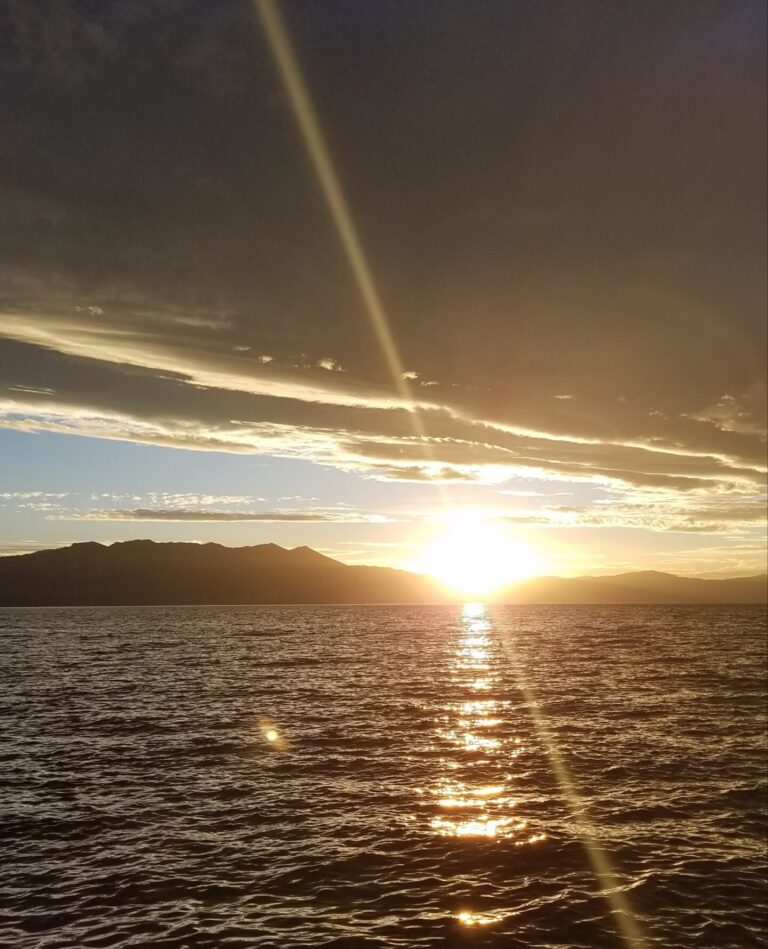

how deep is the ocean,

how high is the sky?

The clock isn’t making that tapping sound.

That’s my pencil eraser hitting

the desk as I flip it between my fingers.

A rectangle of light that moved

down the side of Mrs. Bishop’s desk

now climbs up Annie Taylor’s leg,

makes it’s way to the hem of her pleated skirt.

She doesn’t notice the sun’s design on her.

Everything has designs on her,

but she’s oblivious to it all.

She’s bent over her desk,

defining words and identifying triangles—

equilateral, isosceles, and scalene—

by their acute, obtuse, or right angles.

For all she cares, the sun can have her.

She shifts in her seat

and the sun reaches her knee,

claiming her.

On land, Annie’s better than me.

I haven’t much meat on my bones yet.

When I walk, my ankles knock each other.

Annie’s not afraid, like I am,

that she’ll melt and become a free form,

shaped like the rays of light which spread

into configurations that can’t be named

as they caress the water in the pool.

Just hours before, I swam

among those patches of light,

skimmed the bottom of the pool,

followed it’s contour

deeper and deeper, sure I’d explode,

as I almost do, until rocket-like,

I thrust myself up from the deep end,

erupt from the surface

in a froth of bubbles,

and gasp, sucking harsh oxygen

back into my lungs.

This is the test I pass,

droplets of water flying from me

in a spray of liquid diamonds,

rising into the dry heat

of a Phoenix morning

victorious

because the water

didn’t breach me,

didn’t claim me,

didn’t keep me under.

FAST LAUGH, EASY TOUCH

I think about the things I don’t know about him,

even though we drove the California coast

from the first mission to the last

and dipped our fingers in the holy fonts

of Spanish architecture and fictions

we couldn’t tell from truths.

I think about how we pretended

he’d grant the indulgence for me to buy my way

out of the knot of that tangled brown summer.

I think about the things I could have said,

the things that make me wish he’d left sooner.

I think about the things he took

or asked for without a second thought,

things that built a bottleneck of unspoken words—

sentences left out and conversations left in.

I think about the things he did say, how his long leg would hang

over the front seat of his Firebird, or how he laid me down

on his bathroom floor and covered me with soap flakes

before adding water and himself and we could never stop

seeking that again—

that fast laugh, that easy touch, our fast laugh, our easy touch,

that rumbling together.

I think about my need to rearrange

the events of his departure.

But always I see that trip to the missions.

Both of us as two dried pods in hot wind,

bumping and rattling against each other,

hoping enough agitation would force open our shells.

Always I see I’m stuck on seeing those pods

as an image I use to erase my regret of squandered time.

But I can’t forget—

I can be looking in the mirror in my bedroom,

my carpool tiring of waiting

for me,

the driver tapping the horn, and without a second thought

I no longer care who might know if I give away

what I have left of another city promise.

Looking at my reflection, the carpool driver honking,

little camaraderie left behind the repeated notes

of the summons,

it’s not so much the time

that I’ve lost

as what I can’t forget—fast laugh, fast laugh, easy touch.