Tate Lewis – 3 Poems

Crows

They are not butterflies,

spirits of renewal flapping

newly developed wings,

nor buzzards, spirits of rot

drifting on tattered, black sails.

They are not pin pricked flecks

of death, they simply crave it.

They are the gallery hissing

and jeering and chanting

while they watch us die.

My father used to point

them out, Look

they beat us here—

they are the first to circle

down from the trees

in the morning, beating

their chests and croaking

at the doves,

—we all have something to mourn.

They are always the same,

hunched shoulders and hopping limps,

murders gathering in the roads,

picking at riddled remains

of life, then disappearing

like departing deities—

plumes of dissipating smoke to strange

trees in foreign lands full

of wardrobes storing recyclable flesh

resurrecting from frowzy fields.

I met them at my father’s funeral

where truth is lost in translation.

I asked them: how far they’ve been,

what happens when the body rots,

where is he now,

does a noticing soul ever blind?

They escorted me across the parking lot,

gargling bones.

His Urns

1.

It faced Main Street in the funereal home window

surrounded by clear vases of water, baby’s breath,

tulips, roses, and some scattered succulents.

This was the first time he was the most orderly one

in the room.

I approached his smoothed corners, squared and glossy

but dry—so easy and to slide my fingers across

like seventh grade woodshop class

when I built my own box.

I don’t remember exactly how long he waited

but after we moved to Michigan he followed

and almost everyday he watched me cut, plane, sand,

nail, stain, and finish every single piece, in his wool suits,

until I had an urn.

When I held him his weight surprised me.

Five pounds of bones was heavier than I expected

but where is combustion stored?

2.

After the funereal,

his wife gave me

and my brother a choice:

gold or silver.

Born first, he went home with the gold

and I the silver.

Three thin black bands run around its center,

but everything else about it shines.

The top tapers into a steeple,

ready for worship.

These are his body parts, separated for me:

a finger, nostril, belly button, tibia, tongue, penis,

and that other guy’s liver.

They crowd a chalice the size of a shot glass

or a salt-shaker: he is uniodized, unsalty

salt of the Earth, “no longer good for anything,

except to be thrown out and trampled underfoot.”

This is the Word of the Lord.

3.

My younger sister stored her pieces of him in a Tupperware

under her bed for years until Izzy and I went to visit her in Utah.

After breakfast, we went to Jo-Ann’s

and picked out paint and brushes and a glass

jar and box. That was probably a year ago

and I have yet to see what a craft urn looks like,

but neither has she because

she hasn’t read any of my poetry yet.

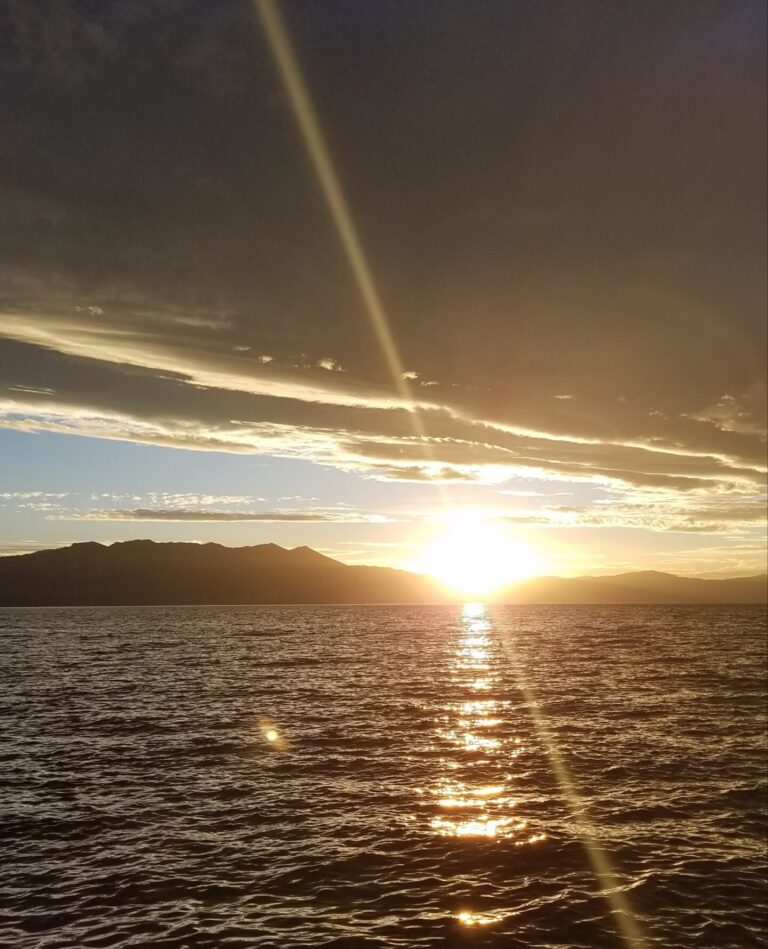

Black Bird

After The Beatle’s “Black Bird”

Drench my skin in bee stings

and squid ink. Separate my flesh

and rip my veins. Clean me,

then keep going. Turn my body

into a canvas and tattoo this pain

on me so I cannot forget.

No color. No brashness. Just black.

Blacker than the quiet light

escaping from the heart of the wilderness

at the sun’s routine turn.

Hauntingly black like a shadow

ducking behind corners, beyond

vision. Like a black bird, greased

and crooked, mother nature’s

drunken muscle. Perch it

close to my ear. Make it murmur

raspy songs in between drags

of cigarettes and pulls of dark

liquor until I fall asleep to

the song my father sang to me:

Black bird singing—

in the dead of night—

take these sunken eyes—

and learn to see—

all your life.

Remind and comfort me,

he always waited for this

moment to be free.